Tuesday Talks: Award-Winning Poet Captures Ineffable Qualities of Poems and Poetry

The Covid-19 pandemic has sparked a renewed interest and appreciation for poets and poetry, leading to more poems that speak to our collective consciousness, and which try, in turn, to make sense out of our troubled times.

That was one of the major themes to emerge from a Tuesday Talk webinar on April 20th by award-winning poet and Cleveland Park resident Gigi Bradford, the former director of the Literature Program of the National Endowment for the Arts, The Academy of American Poets and the Folger Shakespeare Library Poetry Program.

“Over the past year, most people’s conception of poetry has changed,” said Bradford, who also served as the director for the Center for Arts and Culture, the first think tank for the arts. “Poetry is having more than a moment. It has filled a shelf in our collective consciousness.”

Bradford, who has published poems, and essays and edited books, said, “More people seem to be reading it, writing it and talking about it.”

“In times of stress, we turn to poetry because we don’t have an easy explanation and poems can help with the lack of ready answers,” explained Bradford, who earned an MFA in poetry from the renowned Iowa Writers’ Workshop at the University of Iowa’s College of Liberal Arts and Sciences.

As an example, Bradford read a poem by the late American poet Mary Oliver that reflects the pandemic, and which says, in part:

To live in this world

you must be able

to do three things:

to love what is mortal;

to hold it

against your bones knowing

your own life depends on it;

and, when the time comes to let it

go,

to let it go.

National Poetry Month

Bradford’s talk took place during National Poetry Month, named in honor of a line in a poem called, “The Waste Land,” by T.S. Eliot which describes April as the “cruelest month,” ostensibly because the month breeds false hope.

“Of course, we poetry folks have changed that to April is the coolest month,” quipped Bradford, who served on the board of the Emily Dickinson Museum for 12 years and is now the current and founding chair of the Folger Poetry Board.

Her talk also occurred amid the ongoing Black Lives Matter Movement and only a few hours after a jury in Minneapolis, Minn., convicted former police officer Derek Chauvin of murdering George Floyd by kneeling on his neck and cutting off his oxygen. (Bradford read a poem by Terrance Hayes titled, “George Floyd,” near the end of the program.)

Bradford cited an April 12 Washington Post article in which a professor of clinical psychiatry at Georgetown Medical School said, “Poetry can serve as a vaccine for the soul.”

She quoted another writer in the New York Times who said, “Poets have always given voice to our losses in times of national calamity.”

“Poems connect,” Bradford said. “They spark feelings and emotions and soothe something beyond that isolated self we have all been quarantining with. These days more poems are being written that link the individual to larger social movements, which makes a lot of sense in our current cultural movement.”

Bradford acknowledged at the start of her talk that some people have an aversion to poetry, believing, for example, that “poetry makes (them) feel dumb.”

“Do you think it is totally smarmy and full of hearts and flowers and who needs it?” she asked rhetorically. “Do you hate rhyme because it reminds you of nursery school? Do you think poetry is just for the overeducated and underemployed?”

“If so, you are in the right place,” Bradford assured her audience.

Bradford said she would not try to change people’s negative perceptions about poetry. She added, however, “I am hoping you will come to appreciate that the best poetry is an intellectual thrill and an emotional reverberation.”

Bradford offered a few pithy definitions of poetry and writing, quoting Ron Charles in the Washington Post who wrote, “Poetry is not a more difficult way of saying something. It is a way of saying something more difficult.”

She quoted E.L. Doctorow who said, “Writing is like driving all night in the fog. You can only see as far as your headlights. But you can make the trip the whole way.”

Thinking About Poetry

Before delving into specific poems, Bradford proposed seven ways to think about poetry.

- Poetry asks the reader to supply the missing sentiment almost as a co-conspirator with the poet. If a poem tells you how to feel it is not a poem. It is a Hallmark Card.

- Just as not everyone wears a hat, not all poems rhyme.

- Poetry makes its own rules and is indifferent to outcomes. It needs readers who can take a chance on it.

- Poetry requires order, but succeeds best when it rebels against it.

- Poetry brings incongruous things in relationship with each other.

- Poetry rewards empathy. The famous Chinese poet, Du Fu, who lived centuries ago, thanked a friend for sending him some poems by saying, “Reading them – it was like being alive twice.”

- The object of poetry is delight.

Bradford compared poetry to a “detective novel,” saying that poetry allows the reader to come to his or her own conclusions or to find answers or resolutions that may lie within a poem.

“How freeing — no right one answer,” Bradford said.

Bradford read a poem, “This is Just to Say,” written by the famous American poet, William Carlos Williams, to illustrate that point.

I have eaten

the plums

that were in

the icebox

and which

you were probably

saving

for breakfast

Forgive me

they were delicious

so sweet

and so cold

“This is a poem that probably takes place at night, obviously before tomorrow’s breakfast,” Bradford said. “It is addressed to the person who provides that breakfast, possibly and most probably the poet’s wife.”

The speaker in the poem has given into temptation, taking something that someone else would have enjoyed, Bradford said. He asks to be forgiven, but does not say he is sorry, an important distinction, according to Bradford.

“When you say you’re sorry, the onus is on you,” Bradford explained. “You are admitting you have done something wrong. When you are asking someone else to forgive you, you are asking them to do all the work.”

Bradford asked, “Who do we emphasize with – we emphasize with the one who has transgressed. It gives us license to sin and eat the plums.”

Although short, the poem has “layers and layers of meaning,” said Bradford.

Poetry & Sandwiches

Bradford continued with a food analogy to make more points about poetry, comparing poetry itself to eating a sandwich.

“It’s got layers,” she said. “You can taste the bread, the mayo or the mustard, the turkey or the hummus, the lettuce and the tomatoes,” she said. “Separately, they are only ingredients. But together they make a meal.”

Like the sandwich, poems work on multiple layers simultaneously, leaving it to the reader to figure out the different tastes and levels of meaning. To illustrate this point, Bradford read a poem called “Keeping Things Whole,” by 20th-century poet and former poet laureate Mark Strand.

In a field

I am the absence

of field.

This is

always the case.

Wherever I am

I am what is missing.

When I walk

I part the air

and always

the air moves in

to fill the spaces

where my body’s been.

We all have reasons

For moving.

I move

to keep things whole.

Strand started his career as a visual artist, and in this poem he imagines himself in the field – the foreground – of one of his paintings. He is simultaneously painting and trying to erase himself from the easel while commenting on his life in general.

When he walks, he parts the air, disturbing it, but the air fills in behind.

“It is a brilliant exposition on two levels at once because his perceptions are extraneous,” Bradford explained. “To keep things whole, he needs to get out of the way. It is really a fascinating description of the role of individual consciousness.”

When addressing point of view, Bradford presented a poem called, “The Sky is Blue,” by David Ignatow:

Put things in their place,

My mother shouts. I am standing at

The window, my plastic solider

at my feet. The sky is blue

and empty. In it floats

the roof of the house across the street.

What place, I ask her.

“What is brilliant about this little poem is that it makes you realize that point of view is readable,” Bradford said. “This poem is a wonderful stand in of what poetry itself can accomplish, which is making the familiar strange, allowing us to see through someone’s else perspective – someone else’s eyes.”

In this case, it is a child looking out the window, said Bradford.

A Declaration For Justice

Bradford chose a poem by former poet laureate Tracy Kay Smith called “Declaration” to speak to the need for racial justice. The poem, based on the Declaration of Independence, uses a technique called erasure to remove certain words from the document to get the poem’s points across in a powerful way.

He has

sent hither swarms of Officers to harass our people

He has plundered our—

ravaged our—

destroyed the lives of our—

taking away our—

abolishing our most valuable—

and altering fundamentally the Forms of our—

In every stage of these Oppressions We have Petitioned for

Redress in the most humble terms:

Our repeated

Petitions have been answered only by repeated injury.

We have reminded them of the circumstances of our emigration

and settlement here.

—taken Captive

on the high Seas

to bear—

“This is a poem where the space around the words is just as important as the words themselves,” said Bradford. “If any of you like jazz, you know that jazz musicians say the space around the notes is as important as the notes.”

In “Declaration,” Smith employs a similar technique, inviting the reader into the spaces, which helps to amplify the sense of space and loss.

Shakespeare The Rapper

“Declaration” is a contemporary poem, published last year in The New Yorker. But poems written centuries ago can still resonate, and we can, in fact, “find ourselves in them,” Bradford said.

She stressed that poetry is quite varied, not monolithic, often reflecting the times we are in. Rap, for example, is a form of contemporary poetry that is breaking new ground in verse while “opening up poetry to a lot of people,” said Bradford during the question and answer period.

“I think if Shakespeare were alive today he would really be into rap,” though he would probably change certain elements based on his preferences, she said.

Bradford defined a good poem as one that “speaks to you.”

“There could be a Shakespeare poem that you don’t like so it is not a good poem for you,” Bradford said. “But if you find yourself in someone’s emotional core through a poem, it is a good poem for you.”

She urged her viewers to read a poem a day by tapping online sources such as Poetry Daily or the Writer’s Almanac.

“Find poems you like and who knows – maybe you will end up writing one,” Bradford said.

Editors note: Gigi Bradford’s most recent book, published in 2012 and co-authored with Louisa Newlin, a Cleveland Park resident, is called Shakespeare’s Sisters: Women Writers Bridge Five Centuries, a handmade chapbook published by the Folger Shakespeare Library in conjunction with that library’s exhibition of the same name.

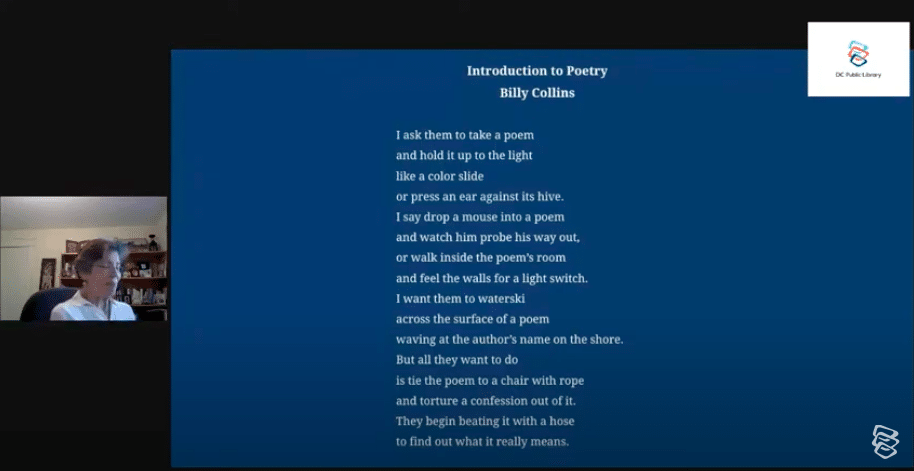

Bradford also teaches highly popular classes on poetry reading and appreciation at Politics and Prose Bookstore in Washington, D.C. She recommends Garrison Keillor’s book, Good Poems, and Billy Collins’ Poetry 180 as excellent introductions to poems.